The Vicarage Cottage was built in the mid 1600s and was constructed in the traditional vernacular mud and stud style.

For many years it was thought to have once been the Vicarage. However contemporary Church records, which list all the Church lands in Billinghay at the time, refer to the Vicarage as a “mansion house”, which suggests a more substantial building, probably of Stone or brick. However, it also lists various outbuildings and “a cottage situated on the vicarage ground” which is probably the building which we see today.

Many parts of Britain had an earth based method of construction, and though they differ from area to area they fall into two main categories, namely Cob and Wattle and Daub. Cob is a solid wall construction of earth mixed with chopped straw and stone fragments and is found mostly in the South and South West of England.

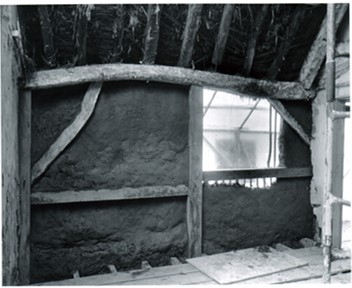

Wattle and Daub consists of a timber frame with an infilling often of woven hazel or willow and the whole covered with mud. Using a frame allows for thinner walls of approximately 25cm as against 60cm for cob.

This cottage is constructed in a type of wattle and daub, known as mud and stud, which is found almost exclusively in Lincolnshire. It is a style that is more economical with materials than most

First a wooden frame, often of oak, was erected. This usually consisted of vertical wall posts (studs) placed at approximately 2 metre intervals. There would be a couple of horizontal rails to stabilise the wall posts and then a wall plate on top. Next a series of laths would be nailed to the framework. Usually 2 laths fixed one above the other would be needed to span the height

Finally the walls would be coated with a mixture of mud and straw (and sometimes cow dung as well!). This would be built up in layers and when dry it would be lime washed and waterproofed with tallow. This would then be quite a solid construction, the walls being up to ten inches thick. To complete the building a plinth of brick or stone about 50cm would often be built around the base of the building to protect the wall posts from erosion and an overhanging thatched roof would be added. The floor would have been of beaten earth. An example of this, which was uncovered during restoration, can be seen by the door into this room.

Mud and Stud cottages were of simple plan. Usually a lobby entrance faces a central chimney stack with a main room on each side. This cottage follows that plan; there were just two rooms to begin with, the hall and a parlour.

Originally most of the homes in the village would have been built in this way. The materials were easily to hand and buildings constructed in this way could last a long time if well maintained. Unfortunately they were very susceptible to fire and many were destroyed in the Great Fire of Billinghay in 1864.

Over the 350 year life of the cottage it has seen many alterations. It would seem from blackened roof timbers that, when the cottage was first built, it had no chimney, although there was evidence that there was once a smoke hood. The original cottage door faced the church, but this was blocked up in the 1700s and a new one was made in the opposite side. Some of the mud and stud walls were replaced by brick in the eighteenth century and a scullery was added in Victorian times. A wooden floor was inserted in the roof of the hall in the centre to provide sleeping accommodation and, towards the end of its life as a family home, the thatched roof was replaced by corrugated iron.

The cottage was inhabited until well into the 1930s, but by the 1980s it was in a sorry state and was being used by the County Council as a store. The last occupier remembered it, without affection, as being cramped, draughty and damp. Expectations of what a home should be like had altered considerably in the intervening three centuries.

In 1985 the cottage was listed as a building of architectural and historical importance, but as far as the County Council was concerned it was redundant and they had applied to demolish it and redevelop the site.

However, it was saved in 1988 when North Kesteven District Council purchased it and planned to restore it and turn it into a village museum

Despite the partial re-building in brick, the front of the cottage, internal walls and roof structure were all original. Some of the brickwork was removed and replaced by new walls built in the traditional way. Because the cottage had been built without foundations, foundations were dug and a new floor put in. To protect the mud walls from damp the new thatch was two feet thick and weighed a total of twelve tons.

Re-thatching revealed the remains of some small rodents whose presence must have disturbed the human occupants over the years!

A pair of flintlock pistols were also found in one of the walls and these can now be seen in Lincoln Museum.

Replacement materials were obtained locally including willow and hazel laths from an old plantation at Branston and mud from the site itself and from the bed of the nearby River Skirth. Fenland around Billinghay provided the rushes and sedge ropes used for the thatch.

Work was completed in 1990 and in June of that year it was opened to the public.

It is likely that over 1000 mud and stud structures in Lincolnshire survived into the twentieth century. Most have now disappeared either by neglect, demolition or behind brick casings. They had come to be considered primitive and there was a stigma attached to living in them.

However things have turned full circle and today in some countries the mud and timber method of construction is seen as a sustainable and “green” building resource for the future! It has high insulation qualities and low cost of materials. Because the materials can easily be found locally it also cuts down on the costs of transport.

Maybe one day the problem of providing low cost housing will be solved by returning to the building methods of our ancestors!